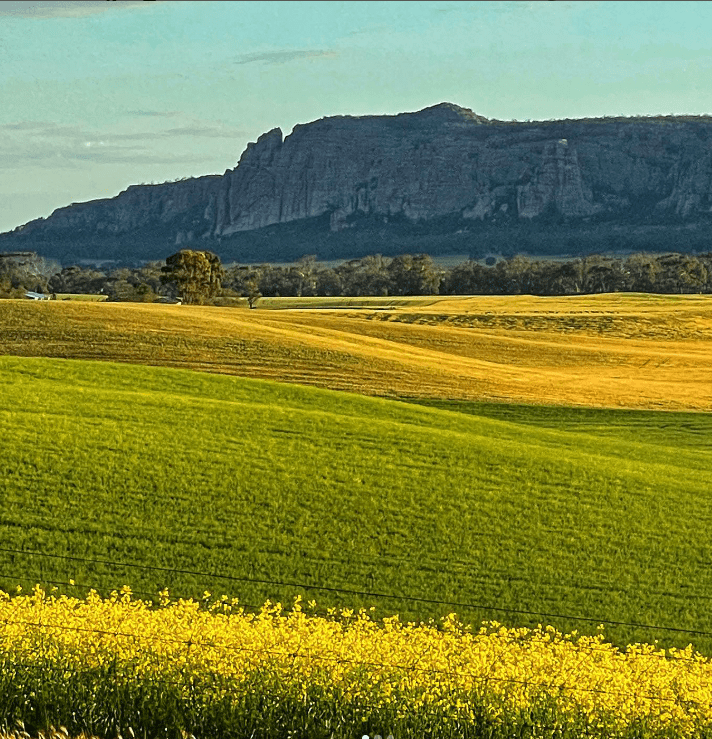

- What Lake Tyrrell – Direl – Victoria’s largest salt lake

- Where – 6km north of Sea Lake in the southern Mallee

- How far – several short walks

- 10 words – salty, textured, flat, vast, light, shade, vibrant, ancient, reflective

There were two good reasons for wanting to visit Lake Tyrrell, near Sea Lake.

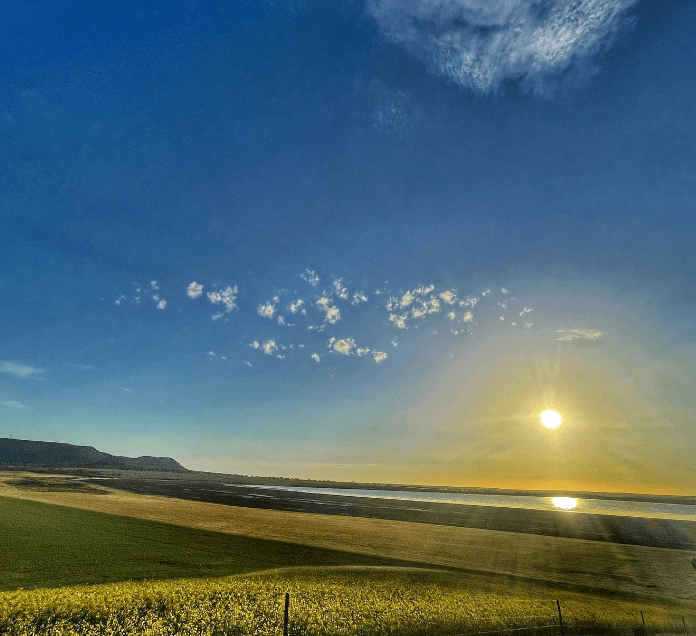

- I love sunsets.

- It is home of Cheetham Salt, a company founded in the late 1800s by Great Great Great uncle Richard, (Mum was a Cheetham) and for whom my great grandfather worked in Geelong.

So, with the prospect of some photography and family history on the agenda I packed my swag for an over-nighter at Sea Lake.

Yes, it is not technically Wimmera, but a close cousin and almost within shouting distance.

Dating back to more than 33,000 years, Lake Tyrell – traditional name Direl – is home to the Boorong clan who were part of the Wergaia language group. Direl means water in language.

Traditional owners have identified spiritual, cultural, social and scientific values unique to Direl, a place where dreamtime was viewed and experienced in both the night sky and its reflections on the lake.

Covering just over 20,000ha Lake Tyrrell – Direl is Victoria’s largest inland saltwater lake. It got salty when sea levels rose about 2.5 million years. With levels 65m higher than they are now, parts of SA, NSW and Victoria, including Sea Lake, were submerged all those years ago.

Today it is mostly fed by groundwater, with some inflows from Tyrrell Creek. The salt is harvested by Cheetham Salt Works, but the lake is also rich in gypsum, alunite and Jarosite, as well as other iron-oxides.

Recently, Lake Tyrrell – Direl, became popular with international and domestic tourists keen to catch its mirror-like reflections of the sky on its shallow water.

I visit in summer when it is virtually bone dry and reflections few and far between.

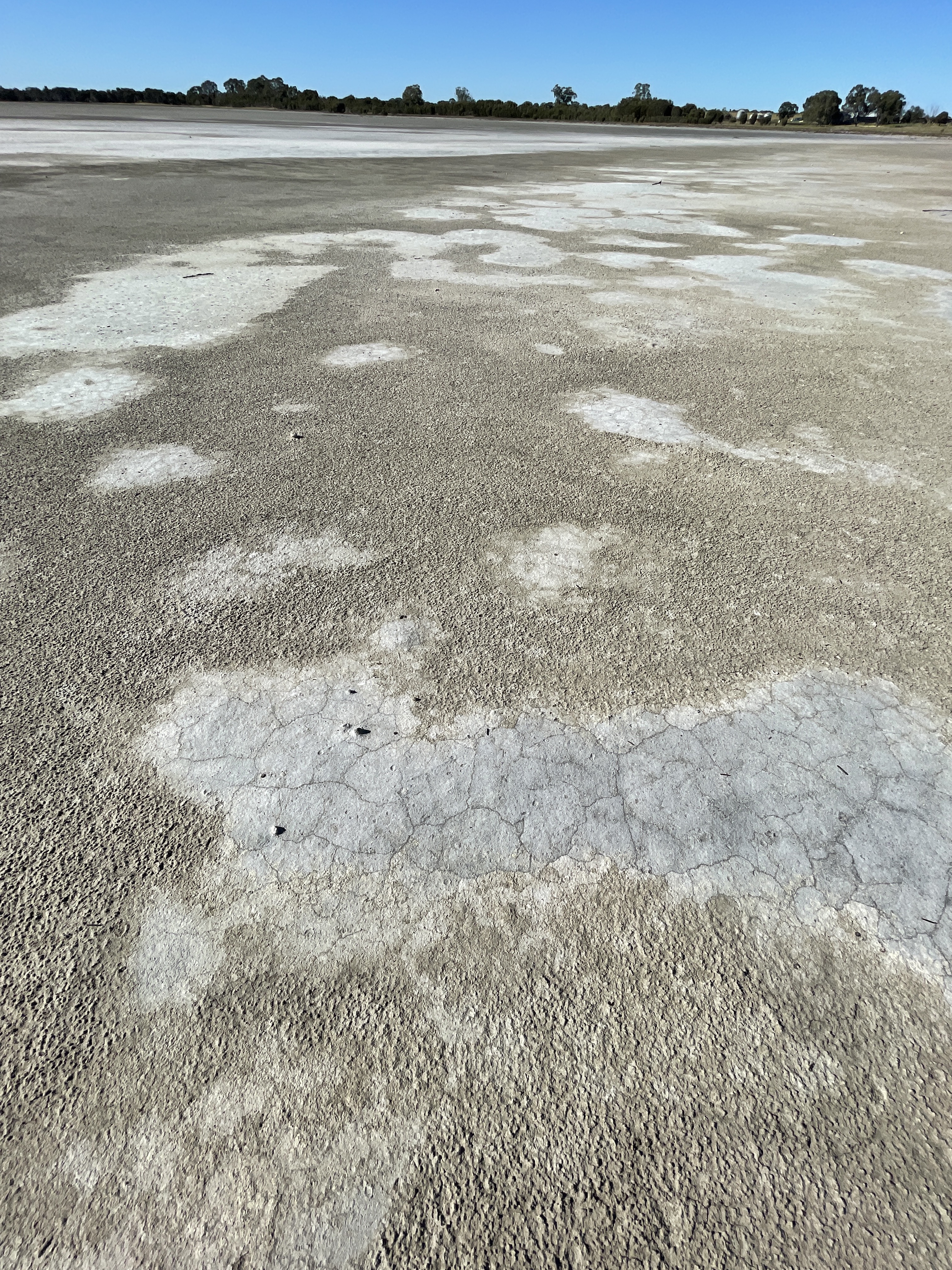

Even without water there are plenty of multi-coloured, textured patterns made from salt and other minerals left after the water evaporates

I head out to the viewing platform and walk along the boardwalk. A sign tells me it is 8-10 times saltier than the sea. No wonder Great Great Great Uncle Richard’s successors decided to come here to source their salt.

It’s also a breeding ground for sea gulls and great place for both Old Man Saltbush and the succulent Samphire – the asparagus of the sea – to thrive.

Tonight, many of these plants look fried and dead but I have no doubt they will bounce and flourish once the cooler wetter weather arrives. I do find patches of ever-reliable green and pink pigface stems reaching for the sky.

It’s a nice walk on a balmy summer evening but the chance of reflections is slim with only a few puddles of dotted between the crusty salt.

Water or not, I’m struck by the lake’s size, the vast sky and the colours and textures.

It’s nature’s version of an abstract masterpiece. I get down low and inspect the lines, lumps and tones.

Old pieces of harvesting machinery lie abandoned but stoically resilient against the corrosive ravages of this place. A line of buried tin fence disappears into the distance, rudely interrupting the flat, open space.

Other parts of the lakebed resemble bitumen roads which have swelled and buckled in the heat, their salty peaks illuminated by the evening light.

We reach the huge, rust coloured ‘Tyrrell’ sign. A bold, manufactured, loud addition to this natural, quiet landscape but it also somehow fits with the backdrop of a blue sky and cotton wool clouds floating behind.

The nearby circular board walk would normally be surrounded by water. No reflections tonight but we get some dramatic shadows on the waves of dry salt in the centre.

People also look at the stars from here to find dreamtime characters including Bunya the possum who fled the giant emu Tchingal and stayed up in a tree so long he turned into a possum. Night skies also reveal Kulkunbulla the two young dancing men and creator Warepil (also known as Bunjil) the wedged tailed eagle.

There are some wonderful shapes to be seen in the lakebed on my return to the car park. White circles with a hole in the middle, an imperfect peace sign and messes of tiny lines crossing over the rust-coloured surface.

The next morning, I return to watch the sun rise where there’s water at another part of the lake.

The sun’s flame transforms chocolate water into gold. It’s like nature’s take on a John Olsen painting as ‘waves’ of salt reveal a tree, an intricate doilie or veins spreading across the lake bed. Shapes, textures and colours show Direl is more than reflections.

I do some more exploring at the southern end and then I head back into Sea Lake to look at the silo and head home.

I did have a look at the Cheetham Salt site but could not get near it, although there is a pic of uncle Dick on the webpage.

Bottom line – I struck out on family history and mirror images photos but on reflection, there are many other reasons to head to Lake Tyrrell – Direl – The colours, its rich Aboriginal history, the space, the sky and the wonder of its unique salty, crusty, harsh and beautiful environment.

NOTE – I have added some images of a brief winter visit in 2019 when there was water, but the sunset was not brilliant.

Source of information about Lake Tyrrell